As part of the Tallinn Fringe, EAMT’s CPPM Master’s program presents their second volume of Läbu (Estonian for a sort of post-party mess), a contemporary solo performance festival. Throughout the program’s run, there are seven different “episodes,” spread out over a couple of weeks, with multiple showings each. Every episode consists of several individual performers, mostly students from the EAMT, presenting unique acts in a variety of venues around town. Due to the sheer variety, there is something that everyone can enjoy—a background in the arts or theater is not required to find these performances interesting. It is easy to think of each episode as a tasting menu at an avant-garde restaurant. If you have trouble choosing between sweet and savory, or if you just like to be surprised, then this format is designed for you.

Today’s offering is Läbu Volume 2’s Episode 2. It is Saturday the 6th, at the EAMT concert and theater house, where four performers take to the Black Box stage offering up an array of solo shows. Ranging from themes of masculinity to social divides to internet anonymity and showcasing a variety of performance styles, this selection of solo acts offers much for audiences to ponder and enjoy.

Starting off strong, Edward Skaines of Australia presents “Body Count,” a piece on trauma and masculinity that explores the complicated space created when these themes intersect. From the show’s description, Skaines’ performance seeks to ask: “How can the fragile and often invisible experience of male vulnerability be exposed and explored through performance?” In his own words, this piece is an attempted on-stage deconstruction and reconstruction of masculinity and its many intricate facets.

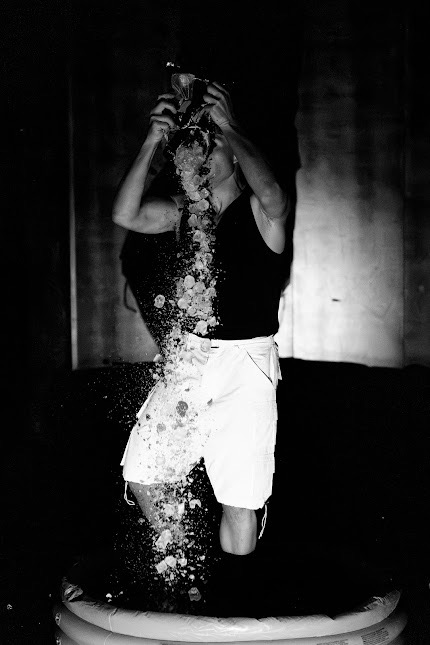

The Black Box is entirely dark and silent as the show begins. The moment suspends in time before a spotlight appears, highlighting Skaines, his every feature clearly defined in the sharp light. As soon as he is illuminated, Skaines begins to shiver rhythmically, his short, uneven breaths the only sound in the theater. His gaze is unwavering and steady, staring straight into the audience. Immediately, the experience feels intimate—there is nowhere else for the audience to look and nowhere for Skaines to hide. Even his shadow, projected behind him, looms large, boxing him in even further and highlighting the theme of unspoken trauma, maybe a literal representation of the shadow self, a part of us that is unfailingly attached to us yet often overlooked, unseen, or ignored.

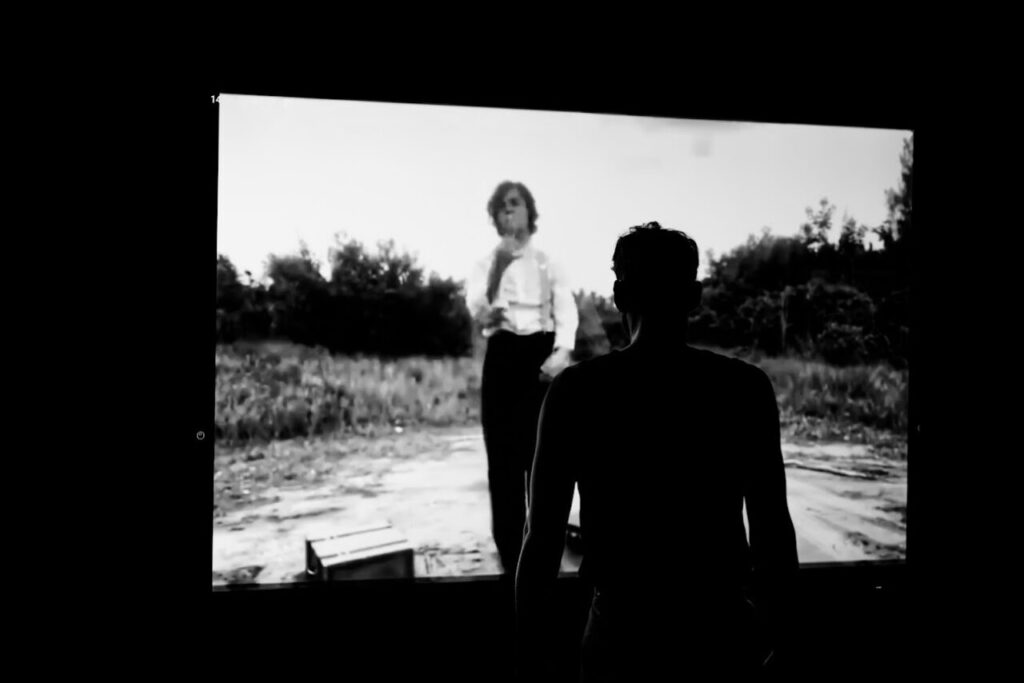

Skaines continues with his rapid shivering as bags of ice fall from the ceiling around him, followed by a small inflatable pool. He dumps these bags into the pool over himself, continuing his full body shivering, which he will keep up without fail for the entirety of his act. He leaves the center stage (and the inflatable pool) only twice, each time bringing out a screen that plays a video. The first video is a taped recounting of different traumatic instances, the second a Charlie Chaplin-esque slapstick routine that plays once forward and then backward, before continuing this cycle in ever-faster repeats.

The physical endurance of Skaines’ performance is not something to be understated, the physical stress he undergoes mirroring the internal stress caused by trauma. The amount of physical control required to continuously shake for nearly thirty minutes while standing in a pool of ice is no small feat. And notably, Skaines is silent the entire time (other than when his recorded self speaks in his first video), perhaps representing how men often suffer in silence. The video itself seems to adds a barrier too—it possibly feels less vulnerable or less threatening than speaking directly to the audience. The final video, one of physical comedy, seems to connect again to the theme of men’s pain, this time maybe suggesting how we often don’t take it seriously.

After Skaines’ act, the audience files out into the auditorium to await the next performance. Groups congregate on couches and benches set up around the room, discussing in a variety of languages the act they just saw. The crowd this evening seems to be an even mix of Estonians and foreigners, and the spectators live up to the “post-mess party” meaning of the festival’s name. Some are dressed up, others dressed down, and some dressed creatively, with one spectator wearing their own self-created pair of 3D printed shoes. Speaking to spectators after the show, they offer up praise and their own interpretations of Sakine’s work. Some focused more on his stage presence and highlight the fact that they could not look away while others speak to the deep subject matter and the topical nature of the performance.

After the intermission, the audience is led back to the stage for the second performance of the night, Maarja Tosin’s “All Dressed Up for the E…”, an Alice and Wonderland-esque offering with the part of Wonderland played by the Internet. This performance is as dynamic as it is at times shocking, which seems to be the point.

The performance begins with an eleven-year-old girl cutting eye holes into a pair of pantyhose before donning them on her head as a rabbit-like makeshift mask. She connects to a Zoom call, where Tosin joins on screen, a riot of curtains draped around her. From here, she applies makeup, drinks down a vase of small white balls, buries herself in a cascade of balloons, and wanders through a labyrinth of fabric and streamers amongst other things. There is so much going on in Tosin’s performance that a week later, I am still contemplating it.

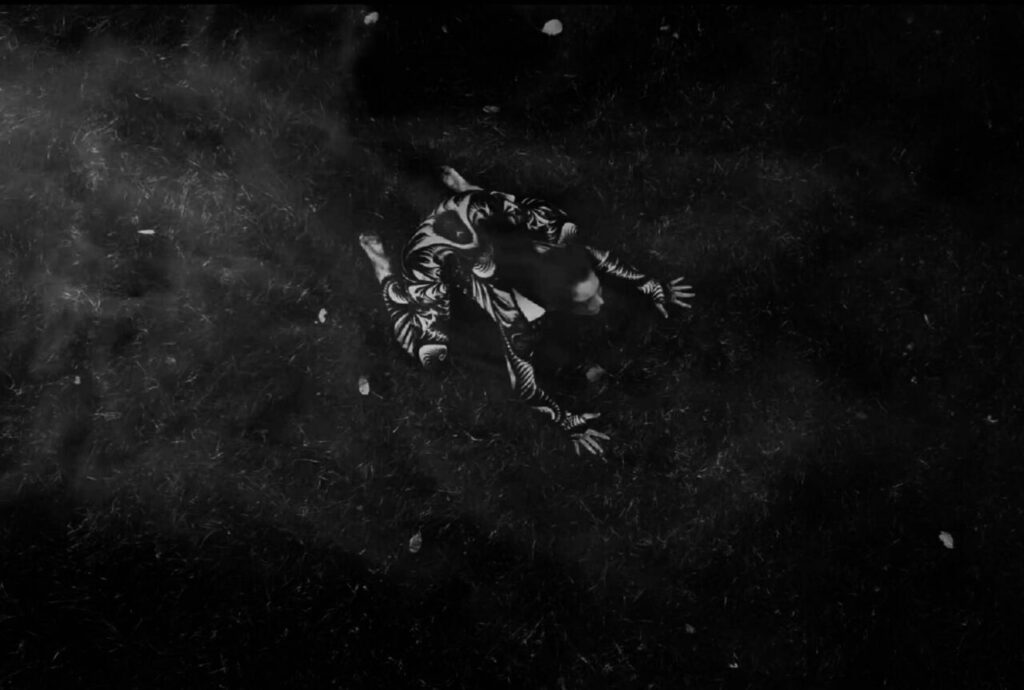

Tosin eventually joins the stage by dropping down from the scaffolding above the audience. She connects to Chatroulette, matching with first one and then another bewildered man who watches as she cuts the hair off her wig, strips, dances, and paints herself with black paint. There is humor in her act, eliciting laughter from the crowd repeatedly, along with too many surprising twists and turns to count. At one point she hangs suspended from the ceiling in an acrobatic display that causes one audience member to let out a small scream. The show finishes with the young girl returning to the stage, removing her mask, and sitting in silence with Tosin. Following this, we ourselves are asked to follow the duo off-stage to take a glimpse into the maze of curtains and balloons where Tosin began her part in the show.

Tosin’s act in general is an avant-garde spectacle, a genre-defying fever dream of an act. It’s like watching a dream sequence from a drug-fueled sci-fi Twin Peaks. The link to Alice in Wonderland is clear with white rabbits and references galore but done with a very modern twist. When asked for their thoughts on the performance, one audience member describes it as “crazy, but cool crazy” while another comments that it was “out of this world.” A third spectator says that they enjoyed it greatly, despite feeling disturbed at times. They muse on the meaning of the show, saying that it felt like a look into Tosin’s mind starting from her childhood—that it is a show of self-reflection on Tosin’s part, of her reconnecting with her childhood self. All the audience members I spoke to really appreciated the attention to detail and the involved nature of the performance. They enjoyed the different formats and types of media used throughout and thought the link to Alice in Wonderland was clever and well done.

After another intermission, the third act of the evening begins, this time featuring Jeson Joy with his performance “Colour Coulour Which Colour Do You Choose.” During the break, audience members were asked to draw folded slips of paper from a jar. The slips depicted a color and an image, directing each spectator to which section they should sit in. Thus begins a performance about segregated societies, hierarchies, and castes.

Joy begins by being asked incessantly by a disembodied voice to pick a color. When he chooses blue, he begins to find orange all around him. Orange papers sticking to his pants, orange paint falling from the ceiling, orange string unspooling from his body. Even a literal orange all add up to drive the point home that he is not inherently in control of his destiny and identity. At different points of his performance, all the stages of grief seem to be present as Joy grapples with being boxed in (literally, the stage is portioned off and a whistle blows when he tries to step outside of the lines). There is an attempt at acceptance and plenty of anger and depression at the helplessness of his situation. The more he fights, the more he cannot escape, and the more he accepts, the more trapped he is. The paradox is clear, as are the themes he touches upon.

Joy draws heavily on his Indian heritage throughout, incorporating dance, music, props, and even news soundbites from his home country to create a truly immersive show. All of the senses are engaged, with incense snaking through the air, water being offered to the audience during one segment, and some spectators being asked to open boxes on the edge of the stage during another. Overall, it is an engaging performance with a profound message. The idea of societal divides is played with through the use of color—the metaphor is neat and clear, an accessible allegory for the audience to consider.

There was a final act as well, “Voodoo Child,” performed by Belgium’s Clarisse Degeneffe, which I was regrettably unable to attend. With another show to catch and Läbu’s Episode 2 running well over its slotted time, I was unfortunately unable to stay to watch what would have surely been another amazing performance.

While the Läbu shows may be finished for this season, they will likely return in 2026. In the meantime, you can still check out a variety of performances put on by EMTA throughout the year, as well as the last offerings of the Tallinn Fringe Festival, which rounds out its season on the 18th of September.

Subscribe to our email newsletter to get the latest posts delivered right to your email.